“The way to power is by giving, not by taking.”

“The way to power is by giving, not by taking.”

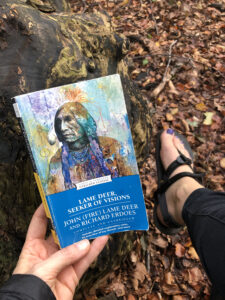

I got it from Sara. She read it, marking the pages where she found little gems of wisdom and insight, and then mailed it to me. And I, in turn, made it one of my twelve English books of the year: Lame Deer, Seeker of Visions by John (Fire) Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes. The book was first published the year I was born, 1972, and the copy I was gifted is an enriched classic published 1994.

“A fascinating story” is a blurb by Library Journal included in the preface. And yes. It is. Spanning high and low, delving into Lame Deers personal life as well as ancient stories such as that of White Buffalo Woman, dipping a toe into the use of herbs as medicine and components of rituals, and much more.

There are several passages I found of great interest, here are two providing me with great amounts of tankespjärn:

“A medicine man shouldn’t be a saint. He should experience and feel all the ups and downs, the despair and joy, the magic and the reality, the courage and the fear, of his people. He should be able to sink as low as a bug, or soar as high as an eagle. Unless he can experience both, he is no good as a medicine man. Sickness, jail, poverty, getting drunk – I had to experience all that myself. Sinning makes the world go round. You can’t be so stuck up, so inhuman that you want to be pure, your soul wrapped up in a plastic bag, all the time. You have to be God and the devil, both of them. Being a good medicine man means being right in the midst of the turmoil, not shielding yourself from it. It means experiencing life in all its phases. It means not being afraid of cutting up and playing the fool now and then. That’s sacred too.

Nature, the Great Spirit – they are not perfect. The world couldn’t stand that perfection. The spirit has a good side and a bad side. Sometimes the bad side gives me more knowledge than the good side.”

“This kind of medicine man is neither good nor bad. He lives – and that’s it, that’s enough. White people pay a preacher to be ‘good’, to behave himself in public, to wear a collar, to keep away from a certain kind of woman. But nobody pays an Indian medicine man to be good, to behave himself and be respectable. The wicasa wakan just acts like himself. He has been given the freedom – the freedom of a tree or a bird. That freedom can be beautiful or ugly; it doesn’t matter much.”

How different this is to the way the culture of the world I perceive myself a part look at it. We strive for goodness, for the perfect gurus, damning each and everyone forever if there were ever a speck of dust marring their perfect image. We do it for politicians and business leaders, for holy men and women and artists, for anyone we want to put on a pedestal.

Being put on a pedestal, never be allowed to slip up, make a mistake, falter. Neither here and now, in the future nor for that matter, in times gone by. Could there ever be a position I’d want less than that one?

The book I am blogging about is part of the book-reading challenge I’ve set for myself during 2019, to read and blog about 12 Swedish and 12 English books, one every other week, books that I already own.

Jag önskar jag läste fler böcker. För att få mig de där tankeställarna i livet. Som att ingen betalar en “Indian medicine man to be good”…

Det får ju en att börja fundera 😊

Ja men exAkt – det är i sanning en ögonöppnare! Tankespjärn i kubik. 🙂

Men wow! Vill läsa! Bara det där, med skillnaden att ingen betalar en medicinman. Och att han (han?) ska känna alla upsen och downsen osv. WOW, som sagt!

Mmm. Det stack sannerligen ut. Inte minst för att det är så tvärtom jag upplever att “vi” i gemen vill att de vi ser upp till ska vara “perfekta”. Som om det gick liksom…

Det där citatet ur boken var så bra… och så viktigt. För vad är det egentligen vi strävar emot. Att vara hela, men ändå stänga ut det som kliar, som känns mindre vackert etc. Jag tror det ligger väldigt mycket i det han säger – även om det är ett rejält tankespjärn. Ibland tänker jag att den nyandliga strävan mot perfektion, faktiskt är skadlig. Jag kan utveckla det om du vill.

Det får du gärna göra – utveckla dina tankar alltså!

<3